Both the gallery project and the chapel renovation read like manifestos, embodying the philosophical principle of parsimony. This concept, as applicable to art as it is to science, suggests that beauty lies in explaining much through little. Here, parsimony means distilling materials and forms to their essence, giving rise to objects, atmospheres, and sensations. The entire collection comprises 3 materials, 4 object types, and 3 colors—a trinity echoing the structure of Japanese haiku (three lines of 5/7/5 syllables), the paragon of poetic economy.

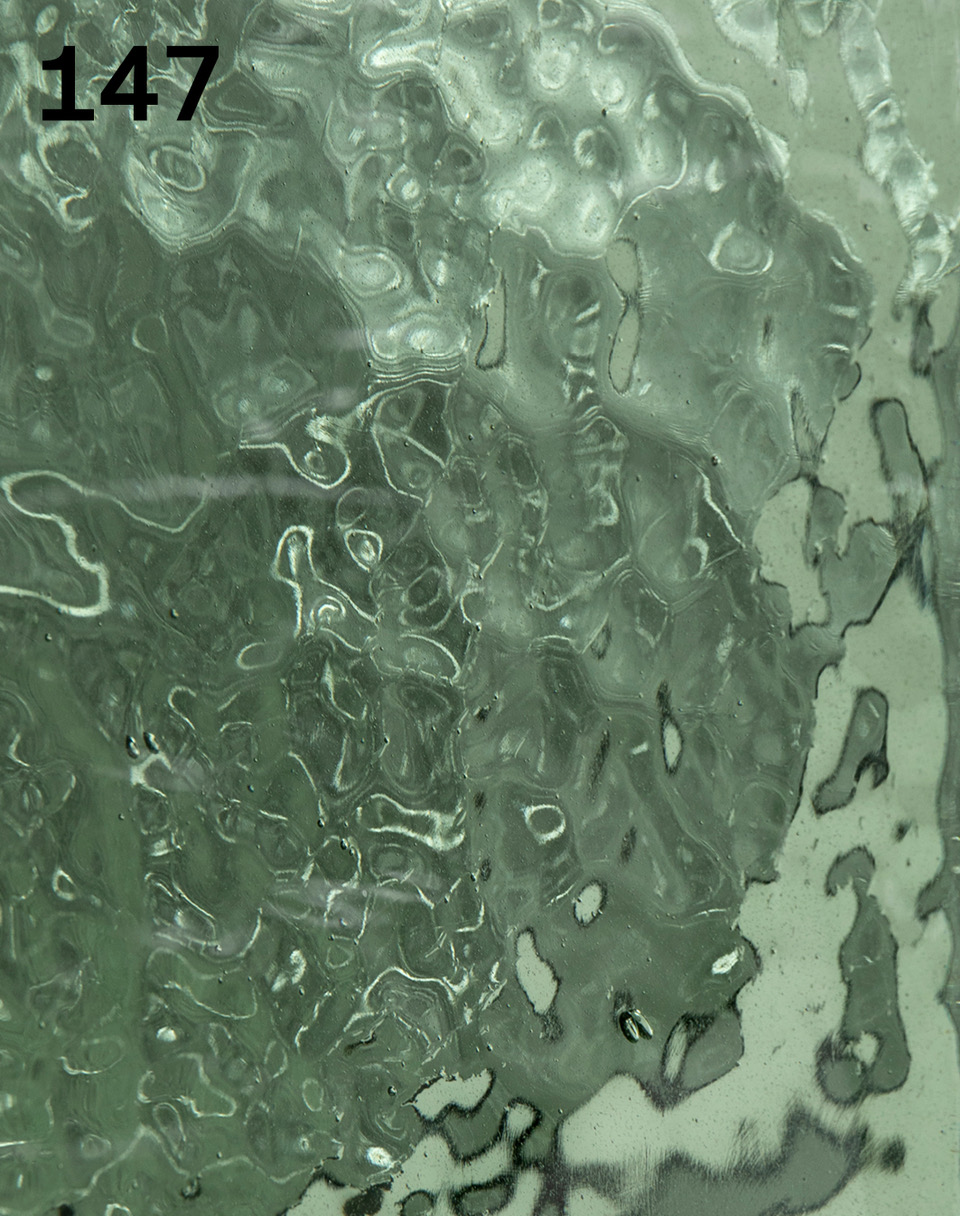

The 3 materials: “Celtic Night of Huelgoat” granite, a dark stone flecked with white, quarried and worked mere kilometers from the Monts d’Arrée. Forged and hammered steel, also Breton, extending the exploration of ferro battuto techniques begun in 2015, celebrating artisanal craft and handiwork. Lastly, cast and silvered glass, created by Venetian maestros, Bouroullec’s collaborators since 2018.

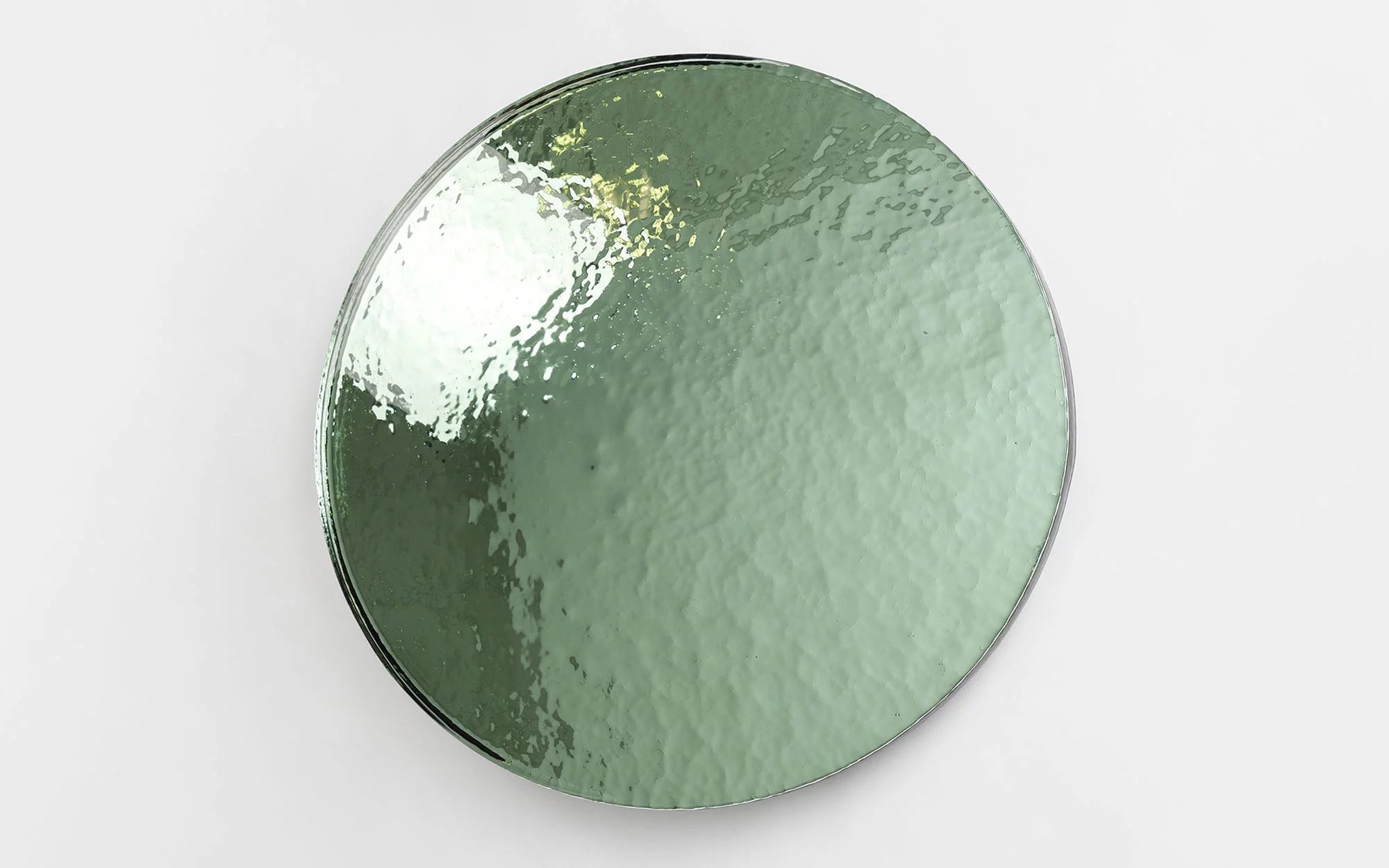

The 4 object types, assembled in thoughtful variations: Towering candleholders (153, 164, and 180 cm) of cast steel on granite bases. Consoles of bush-hammered granite with softened edges, their heft juxtaposed against the apparent delicacy of six legs that extend upwards into candle holders. Cast and silvered glass mirrors, seemingly weightless despite their 3 cm thickness and 100 kg mass. Glass tables—horizontal rectangular mirrors perched on high (75 cm) or low (33 cm) steel frames.

3 glass hues converse with the somber granite and galvanized steel patina. Two colors are newcomers to Bouroullec’s palette: a sea green evoking fluidity, and an almost-black garnet suggesting depth. The third, silver, follows the Flou mirror at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce and its Breton chapel counterpart, serving as both light source and vanishing point, orchestrating space and perspective.

This round coloured silver mirror, centered on the back wall, shapes the gallery space, conjuring a nave-like atmosphere reminiscent of the chapel. It’s an echo, not a replica—while nodding to the pieces’ origins, it allows them to transcend their context, asserting their autonomy and freedom beyond their genesis and initial purpose. The exhibition’s challenge lies in liberating these works from their profoundly situated origins—a landscape of exceptional beauty, etched in Bouroullec’s childhood memory—and their initial roles in celebration, contemplation, offering, and hospitality. By decontextualizing them, they’re free to address questions beyond those that sparked their creation.

Bouroullec’s pedestals—slightly raised quadrilaterals of gray gravel—illustrate this visual and conceptual distancing. The lighter areas they create both highlight the pieces and render them more legible, while elevating objects onto pedestals suspends their utilitarian value. The gallery becomes a neutral, abstract realm, facilitating the transition from public to private, from collective shelter to individual home, from liturgy to daily life.

Throughout this transition, the works maintain their capacity to evoke sensory experiences. Across worlds, they resonate with vibration, balance, magic, and emotion.