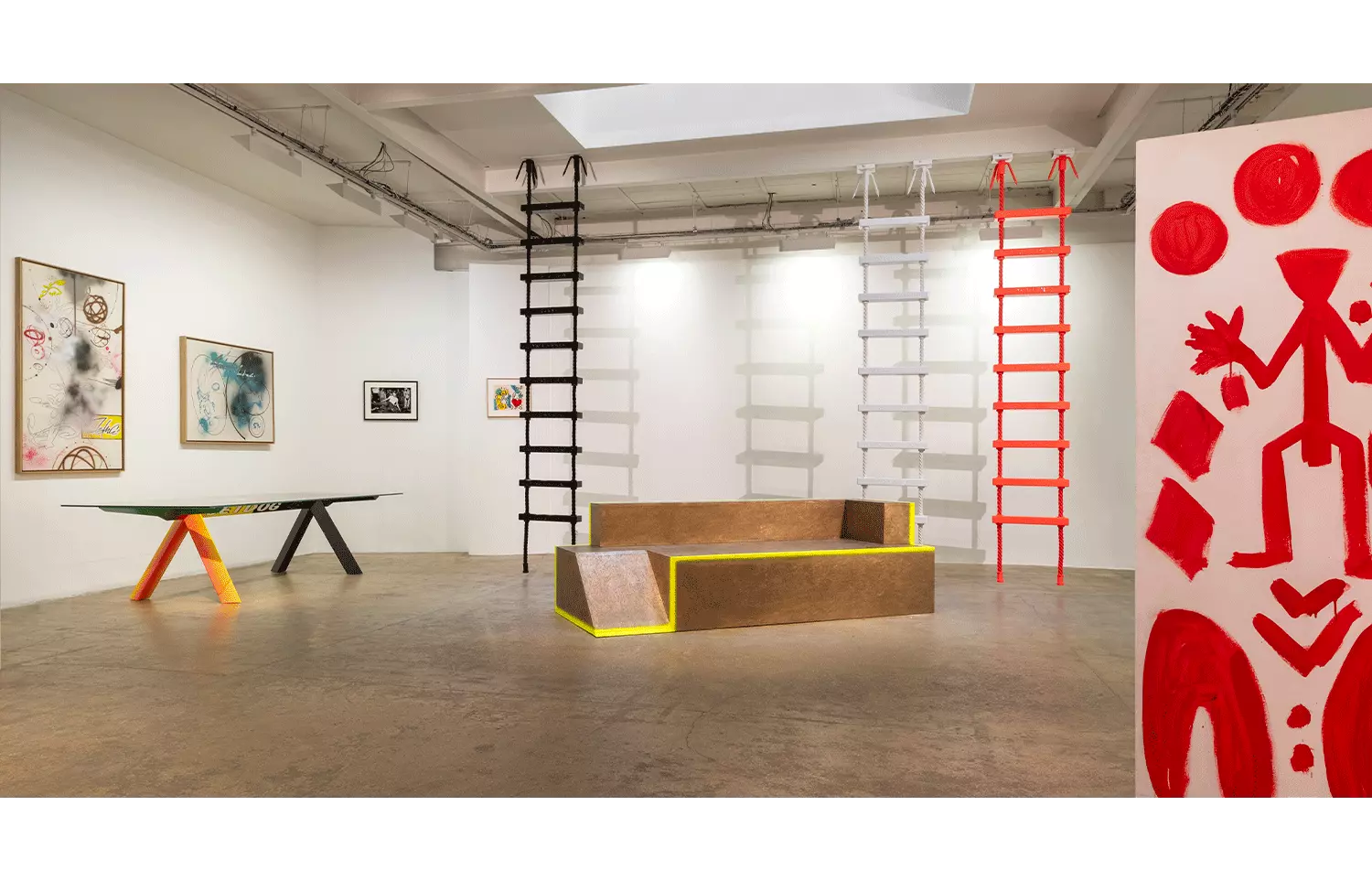

WORLD LEADERS LADDER

Each rung is conceived as a pedestal dedicated to those who have shaped certain aspects of today’s black culture. From Pop Smoke to Phase 2, including Aaliyah, Michael Jordan, Malcolm X, Grand Mixer DXT, and Ella Fitzgerald, it’s a Hall of Fame comprising visual artists, musicians, activists, thinkers, civil rights advocates, jazz and hip-hop pioneers. These names are invoked to help us rise above a mutilated art history peppered with blind spots*. With their anchoring to the floor and the ceiling, and their verticality, these ladders/manifestos are not functional; they are climbed with the eyes to avoid trampling on names, struggles, and imaginings. They function as tools of urban engineering, designed to prevent the ceiling from collapsing, and to expand the mental and intellectual space of the exhibition. The white territory of the white cube is often narrow and self-absorbed. It’s a political and poetic glass ceiling that Virgil Abloh tirelessly sought to crack.

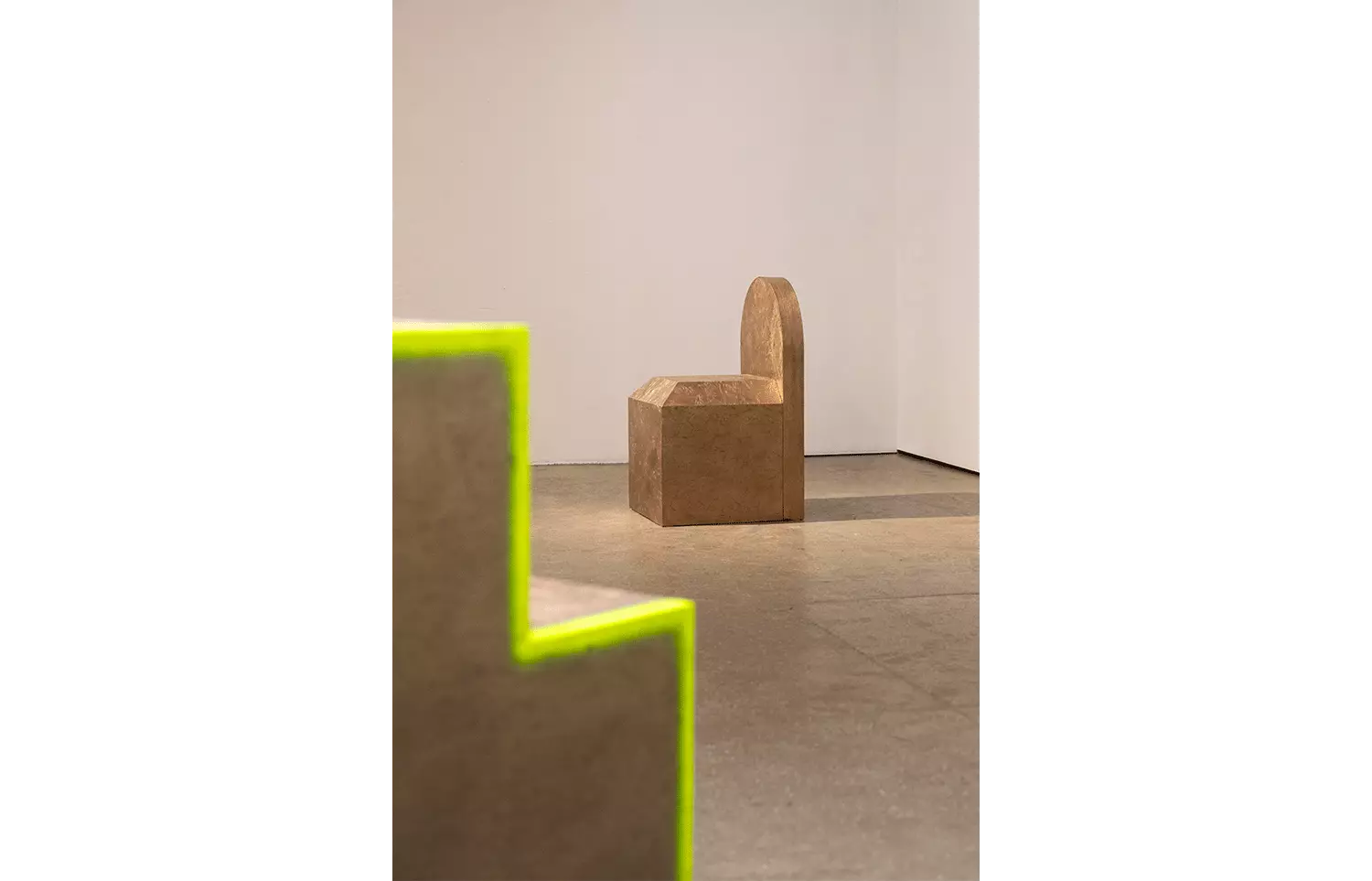

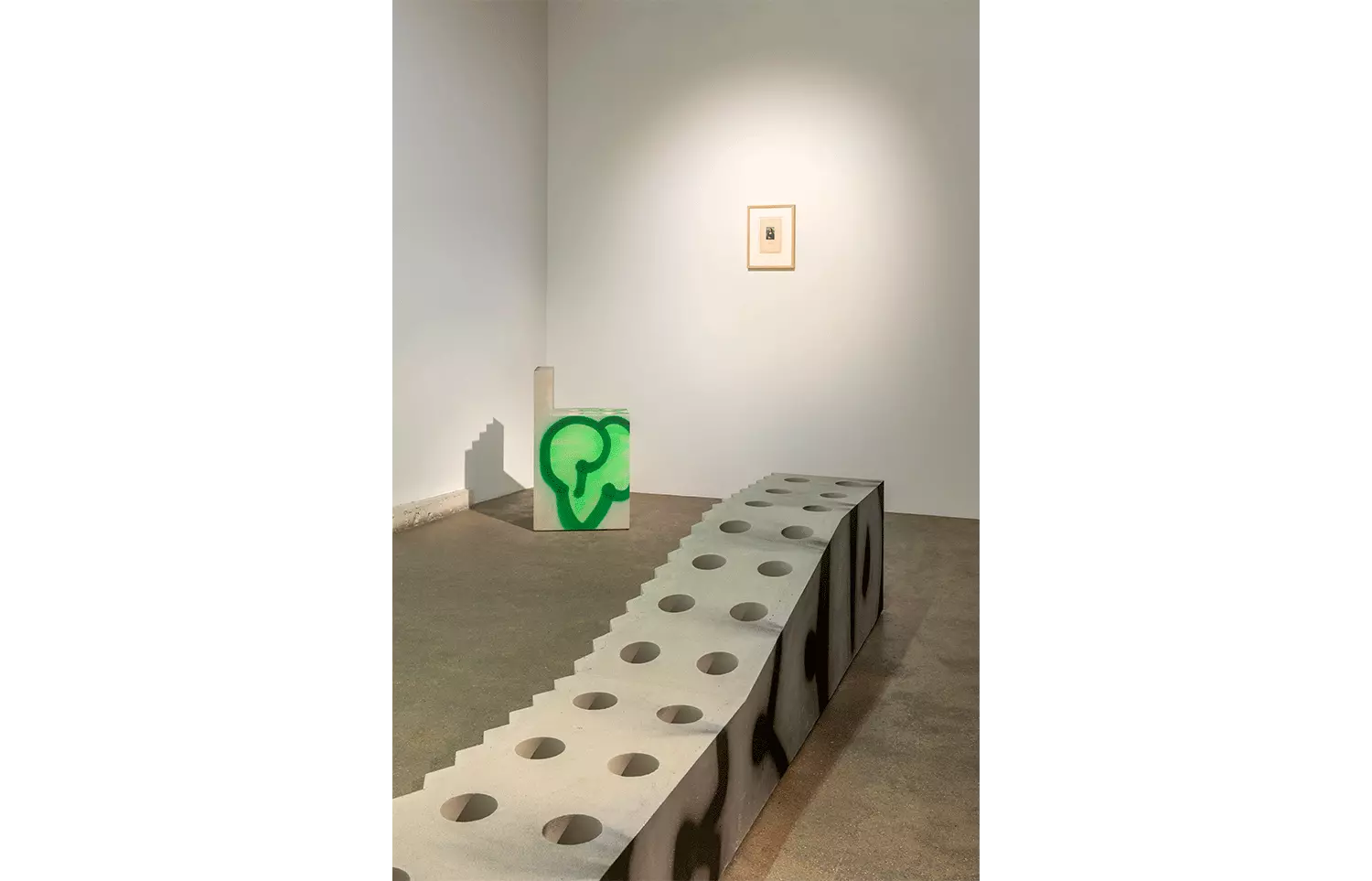

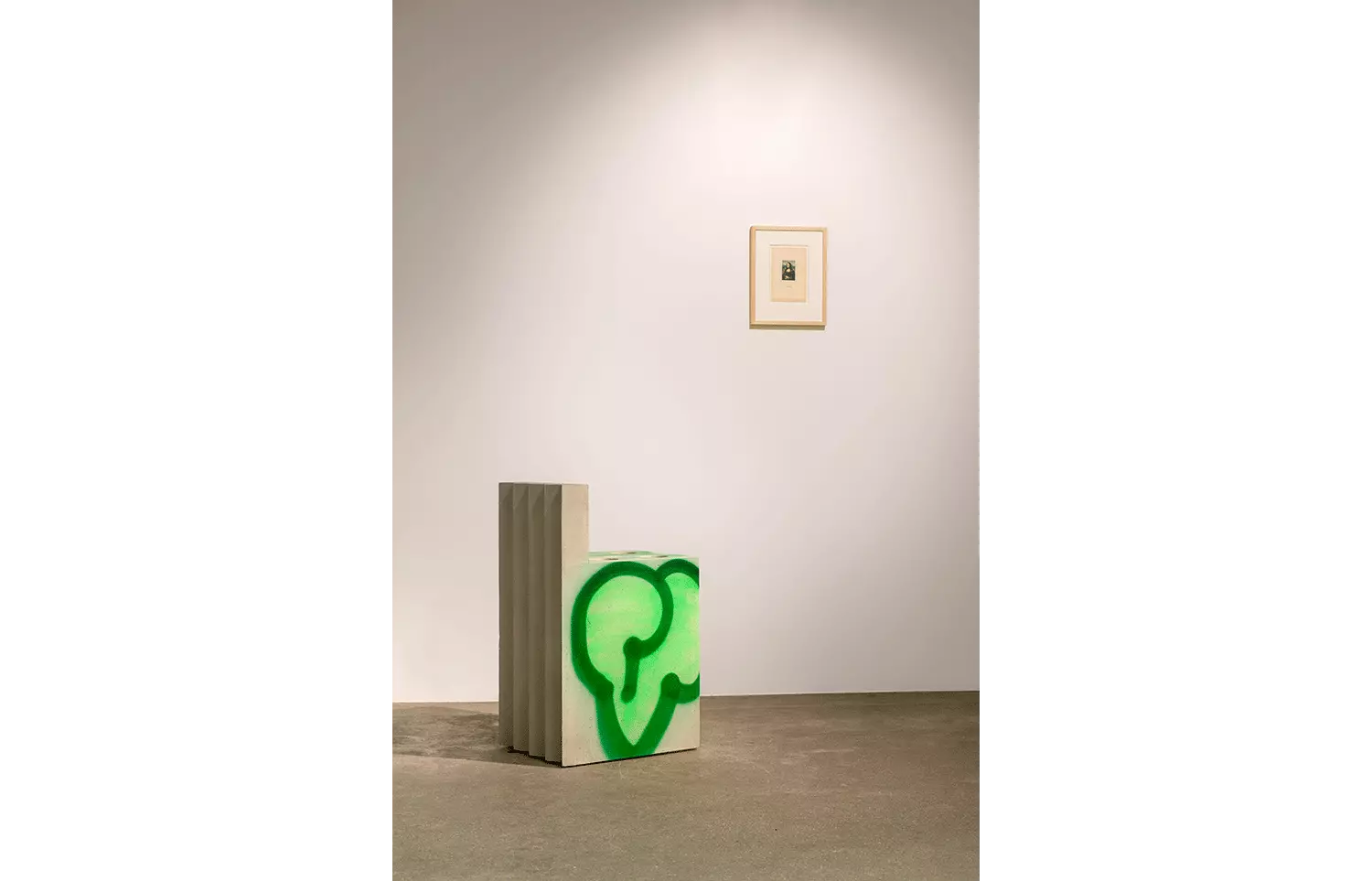

MIDWAY VILLAGE BENCH

Structures with an industrial aesthetic reexamine the history of benches, whether they’re situated indoors or outdoors, in living rooms or public spaces. Depending on various contexts, conditions, and eras, benches serve as meeting spots, places to lie down, collapse, observe the world—or nothing at all. Graffiti grow like unruly weeds, embodying a form of renegade ecology that takes root and spreads through the gaps of the urbanized world. A fluorescent trail calls to mind the marks left by workers on sidewalks, akin to technical and mystical termite symbols. Reduced here to its most minimalist and raw form, Virgil Abloh’s gesture also highlights the sharp edges of these restful structures, often darkened by the wax skaters apply to surfaces to ensure smoother gliding. Within the gray zone that blurs the lines between sculptural and utilitarian objects, Virgil Abloh invites us to close our eyes and let the memory of form, colors, and texture transport us outdoors, onto the streets. To echo the artist’s sentiments, it’s as if the essence of the street is forever alive, even indoors.

VIRGIL ABLOH: ECHOSYSTEMS

“In politics as in art, the goal is to create a shared realm of sensory experience from diverse material and symbolic elements,” wrote Jacques Rancière**. “In essence, it’s an aesthetic pursuit. Aesthetic doesn’t primarily mean something related to art or beauty. It means something related to a sensory experience — the capacity to construct or undergo a specific form of experience by linking perceptions, associating them with emotions, and imbuing them with meaning.”

Rancière’s interpretation of politics as the construction of a unique sensory realm can aptly characterize the life and work of the greatly missed Virgil Abloh. It’s an aesthetic concept that one could synthesize as, borrowing from Rancière once more, a trifecta of “being-together, being-alongside, and being-against.” Being-together connects communities, transcending aesthetic and intellectual boundaries. Being-alongside derives its disposition and modus operandi from the opacity of the margins, where nothing can be reduced. Being-against stands in opposition to oppressive mechanisms. In short, it’s an endeavor aimed at dismantling arbitrary biases.

Virgil Abloh’s intricate, edgeless world finds its origins in a series of distinct experiences. One of a black American child with Ghanaian heritage, raised on the outskirts of Chicago in a predominantly white neighborhood. One of a child brought up on the rhythms and lyrics of Fela Kuti, James Brown, and Miles Davis. One of an adolescent infected with the skateboarding virus — a virus that allows one to traverse the city on wheels, subverting its utilitarian structures and thwarting their practical purposes. A virus governed by a dynamic of vertigo, the body forever teetering between flight and fall. A collective practice, at times criminalized: skateboarding accelerates certain processes of urban decay (particularly at corners, edges, and other playgrounds), disrupts pedestrians, and challenges the city’s serenity.

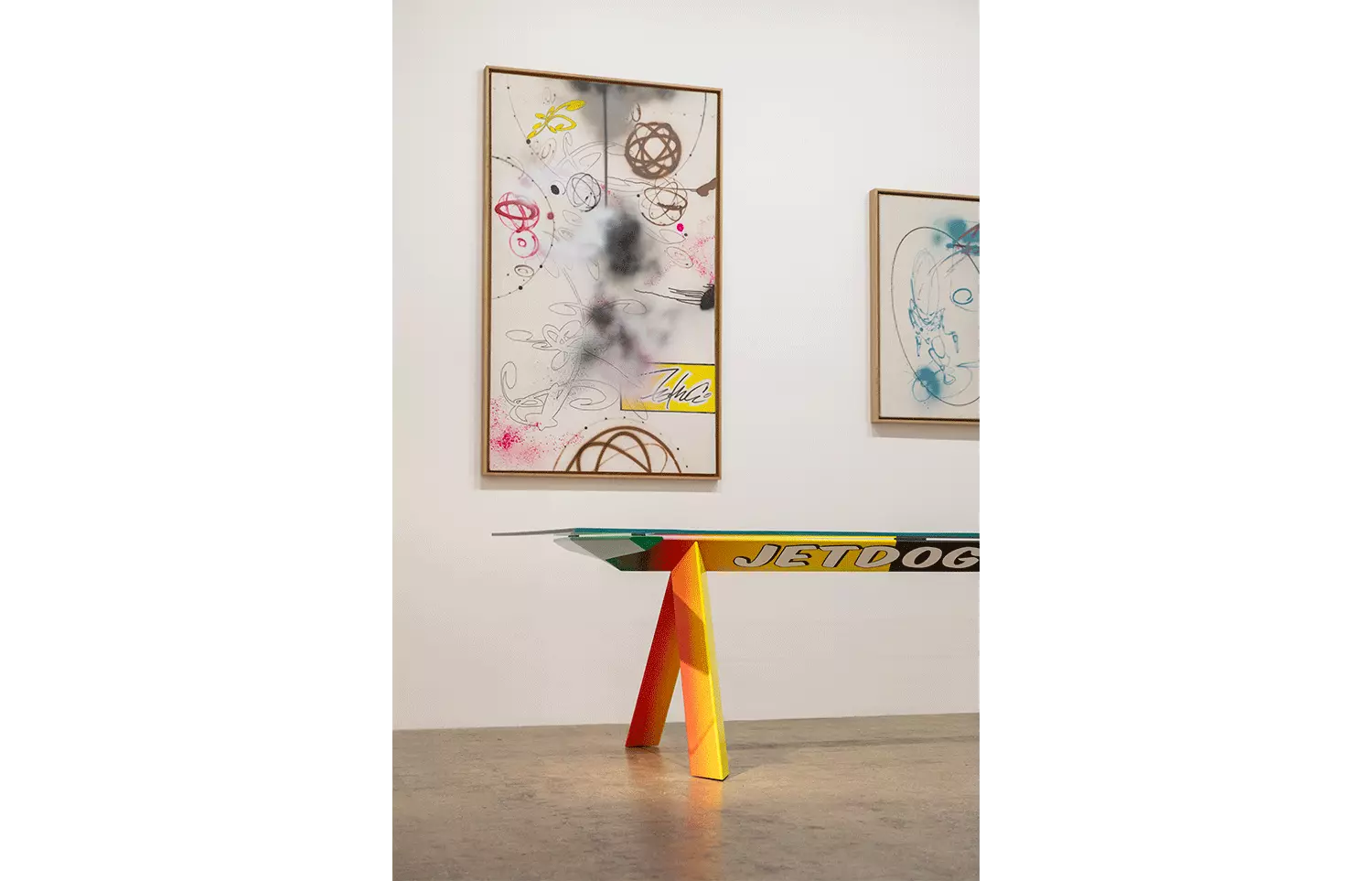

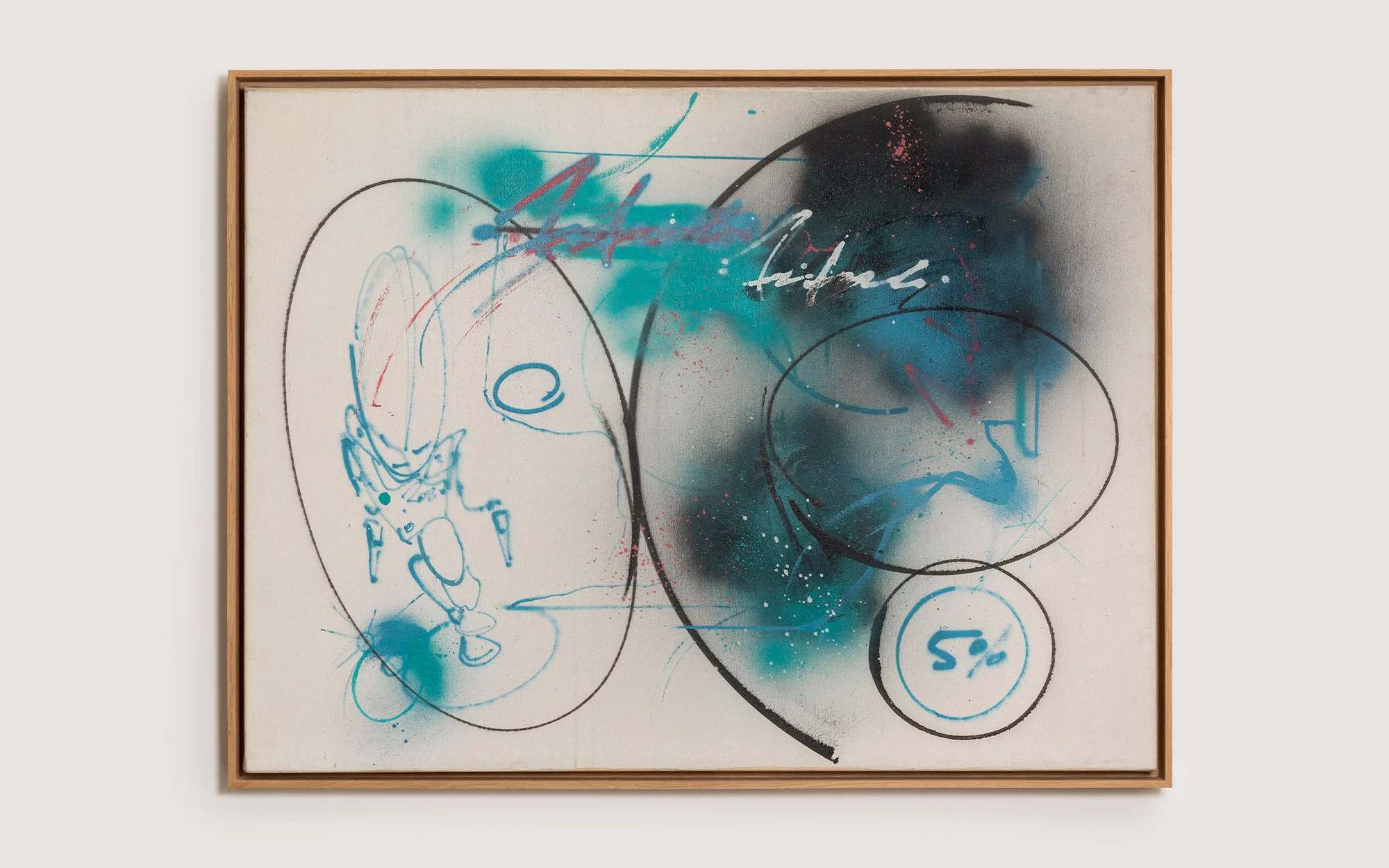

In the continuum of this corrosive and libertarian relationship with the urbanized landscape, the teenage Virgil Abloh became entranced by graffiti—its illegality, cryptic languages, invisible communities, styles, arrows, colors, codes, appearances, legends, myths, and mythos. Graffiti is an attitude, an underground ethos, an imagination of dissent. It traces its origins to the youthful energies of Chicano, Puerto Rican, and African American adolescents who seized spray cans, walls, the interior and exterior surfaces of silver subway cars to inscribe their identities as extensions of their bodies, to depict their stories, their energies, in a city that typically excludes and shatters. Graffiti is a liberating language. Graffiti also influenced the many logos that captivated the young skateboarder Virgil Abloh, through iconic brands such as Alien Workshop, Santa Cruz, and Droors. Graffiti stands as one of the foundational pillars of hip-hop culture, which came to shake, disrupt, scratch, and reshape the history of music to breathe new life into it. Hip-hop is a sentiment. A mode of operation. A way of thinking. “Hip-hop is Black Prozac,” as Greg Tate, a writer and musician who passed away in 2021, put it, “it is a response of black bodies to the post-industrial society.”

Virgil Abloh liked to say that the greatest contribution to black art was the invention of connecting two turntables and a mixer. Much like a DJ, his creative process involved sampling from the realms of art, architecture, design, and fashion, interweaving them into a staccato, syncopated language. In a 2020 interview with Maurizio Cattelan for Flash Art, Virgil explained: “It was during my early days in architecture school that I was told that an architect should be a jack-of-all-trades. That was all I needed to hear. From that point on, I realized that I did not need to abandon my love for Wu Tang, Green Day, Alien Workshop, and Mies van der Rohe, but could apply them all together.” Through a process of deviation, Virgil Abloh aimed to provoke disruptions that would modernize languages, similar to updating software. He introduced his theory of the ‘3%’ in Domus magazine in 2021, stating: “A series of 3% brings the classics to modernity. The 3% ideology has its advantages. It recalls an eye-to-emotion connection in the brain and adds an alternate voice. 2% expands our world view, without pushing our comfort zones to the brink. We’re exposed to the ‘new,’ but not eccentric or disconcerting. What the larger ecosystem doesn’t understand is sampling the ready-made to make anew.” Elsewhere, during an interview with Anja Aronowsky Cronberg in Vestoj magazine, Abloh clarified: “’New’ is a farce to me. It’s a critique intended to keep people like me out. I’m not trying to pretend that I’m inventing something that’s never been seen before. My work exists because I’m inspired by the work of others.”

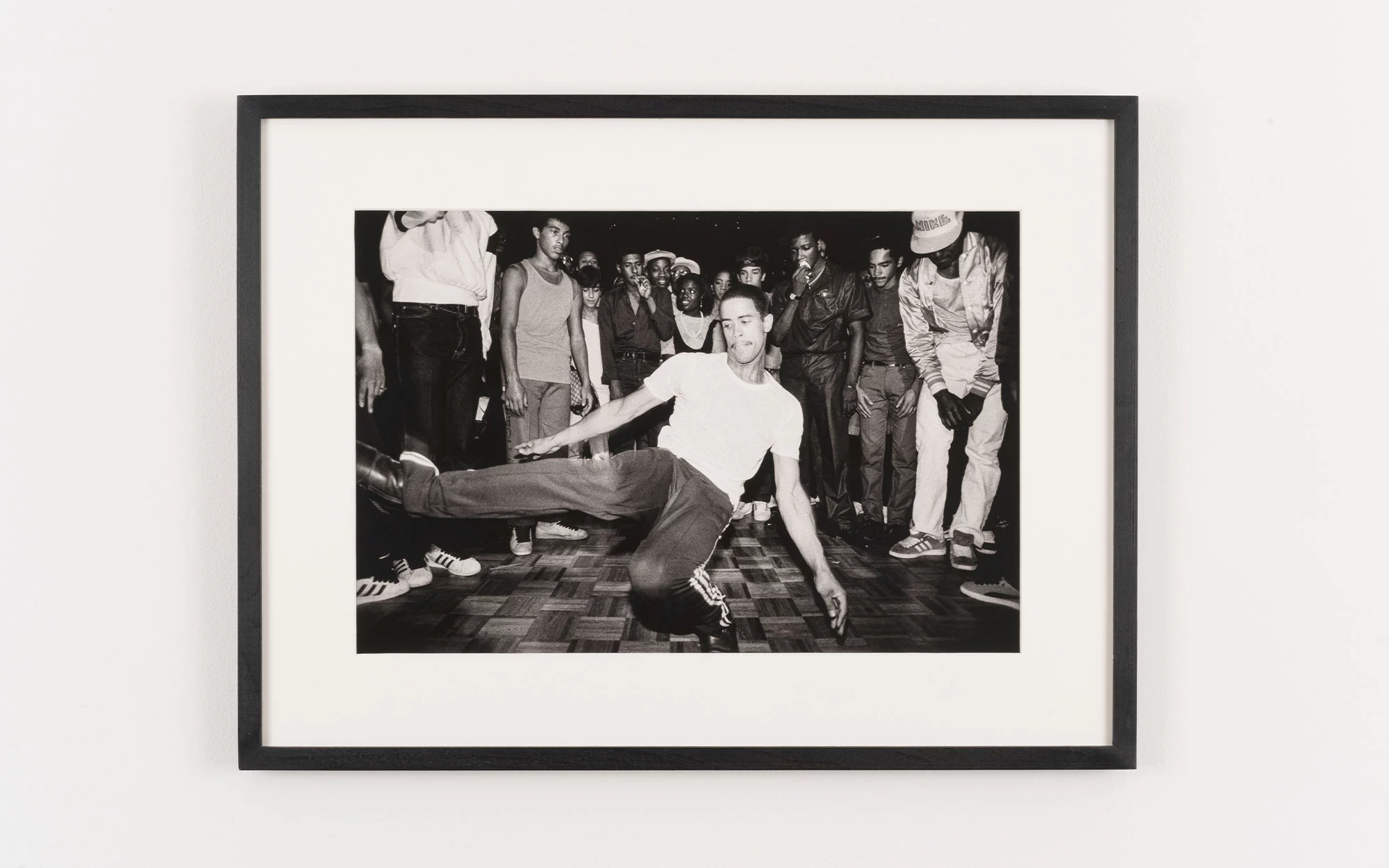

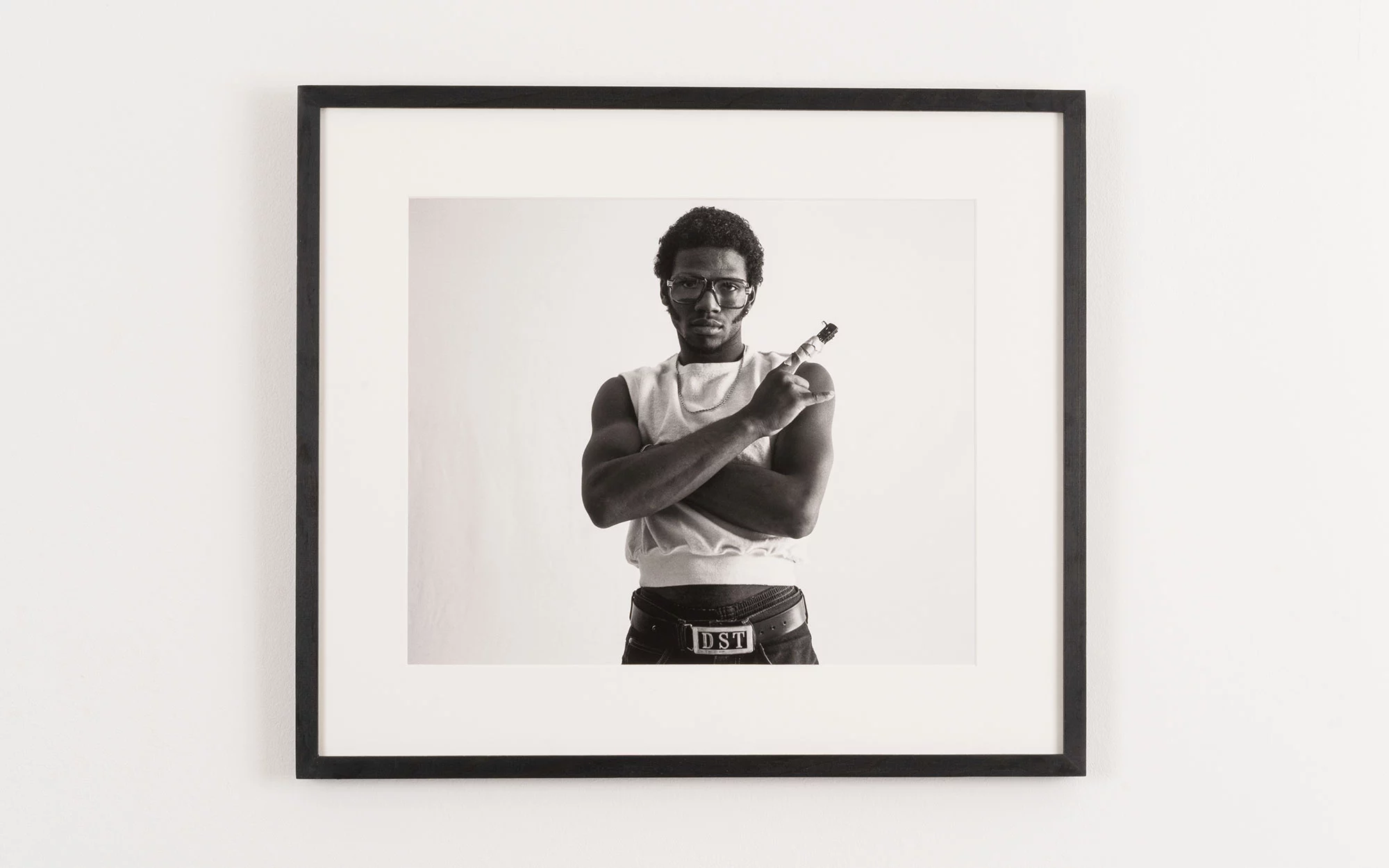

What’s up, Generation? Without irreverence, we can assert that there’s a certain irony in Virgil — the same irony that characterized the work of the man he regarded as his greatest advocate, Marcel Duchamp. There’s also a beat and a scratch, reminiscent of Grand Mixer DXT, captured by Sophie Bramly in the vibrant chaos of 1980s New York. There’s that verbal ambiance, the subway script that has been evangelizing the public space since the 1970s, thanks to Futura 2000 and his contemporaries—an era immortalized through the lenses of Martha Cooper and Bruce Davidson. There are those bold, fluid lines, a visceral impact that resonates in your retinas, as witnessed in the works of Penck and Keith Haring. There’s a taste of Pop Shop, and the essence of logos (in the Greek sense, λόγος – meaning speech, discourse, reason, as well as in the graphic sense). There’s the volatile impulse of Pablo Tomek, the precision of Dondi White’s black lettering, the playful writings of SAMO, which stands for ‘same old shit,’ created by Basquiat. There’s also the architectural perspective of Gordon Matta Clark—an inclination to dissect reality to observe and reveal its shadowy facets—along with the radical lines and logo-inspired colors by Konstantin Grcic, the codes of Erwan Bouroullec, and the subversive strategies of Jerszy Seymour and Tom Dixon. These are just a few artists, among others, who contributed to shaping Virgil Abloh’s language, and they have come together here in friendly collaboration, supported by Jerôme de Noirmont and Noirmontartproduction, Clémence, Didier, Clara Krzentowski, and the entire team at Galerie kreo.

In his work titled Echolalies – an essay on the forgetting of languages, Daniel Heller- Roazen explains that language is always an echo of another, forever bearing witness to it. This is precisely what Virgil Abloh referred to as authenticity: “something that has roots or origins in a specific past.” As such, Virgil Abloh functions as a search engine, an underground, enigmatic resonance that echoes the past into the present.

Hugo Vitrani